The community of Benedictine monks resembled a small, self-sufficient state or city. Within its walls the monastery contained workshops, farms, gardens, and a mill, to ensure that it was relatively independent of the outside world. This insular community was governed by various monastic officials, under the direction of the abbot. Saint Benedict conceived the religious house to resemble a family, of which the abbot held the place of father, to whom the members of the family owed affectionate respect and obedience. The abbot was chosen by the votes of the monks, and the principles that guided him in ruling the monastery are amongst the most important and useful laid down by Saint Benedict. Though the abbot had the right and duty of ruling and watching over each individual member of the religious community, he himself was subject to the provisions of the Rule, and was bound to live the common life of the brothers.

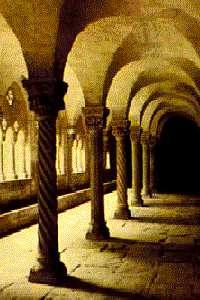

The monastery’s buildings were intended to be in a rural setting or at least separate from any city, enclosed by walls, and containing everything that the monks could need, within reason. The monastery was to be the school of divine service and the “workshop” where the monk was to labour at the spiritual work of his vocation. Saint Benedict admonished his followers to root out their vices and to strive to keep the ten commandments.

The entirety of Benedictine monastic life revolved around the Liturgy, or Divine Office. However, in addition to the Liturgy, the monks were to be occupied in manual labor, and reading. Manual labor was not merely labor in the fields; it also included the exercise of any art in which they had a skill or proficiency that could be sold for the benefit of the monastery, or which could be useful for the common good. The entirety of Benedictine monastic life revolved around the Liturgy, or Divine Office. However, in addition to the Liturgy, the monks were to be occupied in manual labor, and reading. Manual labor was not merely labor in the fields; it also included the exercise of any art in which they had a skill or proficiency that could be sold for the benefit of the monastery, or which could be useful for the common good.

The time devoted to reading and to intellectual studies in general varied according to the period of the year. However, the hours after Vespers, from three to six o’clock, and Sundays as well, were set apart for study.

|